- Home

- Alexander Macleod

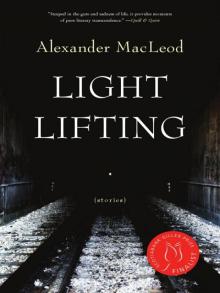

Light Lifting Page 7

Light Lifting Read online

Page 7

I come to relieve her. 10:30 at night. Freezing outside. Other things will happen, but we will never live clearer than this. I take off my boots. She puts hers on. Car outside waiting in temporary parking. Meter running. The heater will stay warm if we switch fast enough.

She just went down, she says. Probably be up for something to eat in two or three hours. New bottle of formula in the fridge at the nurse’s station.

Okay, good. There’s spaghetti waiting for you.

I hold her. All her weight collapses into me and we both cry. Quiet empty corridors in the hospital. Nothing happening. All the overhead lights turned down.

When are they going to let us go?

I don’t know. Have to wait till they say something.

She puts on her winter coat. Turns to leave.

I move to the chair. The upholstery is hard blue vinyl. Cleaning staff wipe it down every morning with a spray bottle of disinfectant. I push it back so the recliner part kicks up. It is about two-feet wide, hard metal support bars running below the surface. You can go down, maybe, but you cannot sleep here. The place where you wait for the next day to come.

I get one of the thin pillows from the shelf in the bathroom. Look up and see her at the end of the hall. Waiting by the elevator. Her head shaking. The numbers descending. I call her name as I move, almost run, down the corridor in my sock feet. Meet her on the way. Kiss.

Stay, I say.

Please stay.

She smiles.

We go back. Squeeze onto the vinyl chair. Her legs between my legs. Arms hanging over the side. Heads touching. Everything forced together. Darkness in the room. Our baby makes no sound. Only the bulb from the machine now. Inscrutable purple light flashing on the ceiling. Like a discotheque, maybe, or the reflection of ancient fire in a cave.

Light Lifting

Nobody deserved a sunburn like that. Especially not a kid. You could see it right through his shirt. Like grease coming through waxed paper. Wet and thick like that, sticking to him. Purple. It was a worn out, see-through shirt and the blisters he had from the day before had opened up again. Now they were hardening over for the second time, sucking the fabric into his back. I tried not to think about him taking that shirt off. He’d have to rip at it quickly – like a bandage – and that would tear away any of the healing that had already happened. Half his back would go. He had a sunburn bad enough to bleed.

I saw it coming the day before and I probably should have said something and stopped it. It was bright. One of those clear afternoons where there’s just enough of a breeze to trick you into thinking it’s nice and cool. On a day like that you can forget that the sun is still up there, on top of the breeze, still coming straight down. Most people have been caught at least once by a trick day like that and it’s worse now. Now it’s over before you feel anything. You can get permanently hurt if you don’t pay attention.

I watched it happen. I watched that burn going into him – the pink blotches moving across his shoulders and down the backs of his arms. He was turning colours right in front of me and I didn’t say a word. Instead, I thought about how it’s strange that you really can’t feel a burn like that when it’s going in. Or you feel it only like a nice comfortable kind of all-over warm. Everything seems fine when you’re out there in the daytime, but at night – when a bad burn starts to come out – that’s a totally different thing. That’s a special kind of trouble. I’ve been there. Probably everyone’s been there.

First it’s nothing. You flip over on your stomach and just try to stay still. You pick that one steady position and try to hold it. But it gets worse, and even though you take the cold bath and pile on the noxema, you still think you’re going to come bursting right out of your own body. Your skin feels too tight. In the end you have to give up on sleeping because now it’s four in the morning and you can see the sun coming up for another round. Every time you breathe there’s a separate stretching pain.

I let him burn because I thought I’d never see him again. But when he came back the next morning – when he came back again, all scorched like that but still ready to go – that turned me around on him for good. I felt sorry for him now and I kept thinking that some of this was my fault. I felt like I did it to him myself – held him down and poured boiling water all over his back or pushed a plugged-in iron onto his skin. He had no way of knowing what he was getting into. His name was Robbie.

When Robbie came back on that second morning he didn’t talk to anyone. He just did what he was told and kept nodding his head all the time. But at about eleven, when the real heat started up and the other guys had their shirts off, it looked to me like he was going to try again. I saw him tugging at the neck of his T-shirt, thinking about it.

“For fuck’s sake,” I said. “Just sweat it out for a couple days. You take that shirt off today, you’ll be in the hospital by tomorrow night. I guarantee you’ll be in the hospital.”

That was the first thing I ever said to him.

“It’s okay,” he said. His voice was flat and calm, like he already had this all figured out.

“I’m prepared for it today,” he said. “I bought sunscreen last night. A sixty-five. Nothing can get through that. I’m ready for it today.”

“Sixty-five.” He said that again, slowly, stretching it out. Like he was amazed. Like sixty-fucking-five was the biggest number in the history of the world.

“Never knew they went that high,” he said.

He had the lotion in his backpack and he took it out and showed it to me. There were two palm trees growing out of a little yellow island on the bottle. He wanted to do it right there. Take off his shirt and reach around and slather himself up. He took off his gloves, wiped the dust off his hands.

“Wouldn’t go like that if I were you,” I said. “That shit will be worse than anything the burn can do. Oil in your hands doesn’t go with bricks.”

He looked at me like I was joking with him.

“Do what you want,” I said. And I held up my hands like I surrendered.

“I’m only telling you the two things don’t go together. When that grease sinks in, you can’t get it out. Not like it’s sticky, but it gets right in there and messes up your hands. Softens them. Makes the skin split. Doesn’t even hurt at first when your fingers start bleeding, just feels wet. But by the end, your palms are all shredded up and the tips are worn right off your fingers. Goes right through your gloves.”

Everything I told him was true. When you wreck your hands they never come back the same way. I got my fingers so bloody and infected once that when they finally healed over again I could still see little chunks of stone trapped under my skin.

Robbie kind of smiled and he shook his head back and forth. He put the cream back in his bag.

“No lotion,” he said. Then he looked straight at me and for a second I thought he was going to quit right there. I could see two little veins pulsing in the middle of his forehead. But he didn’t go for it. He looked up at the sky like he was trying to figure out if there was a better place to stand – a place with some shade.

“They say it’s supposed to be very hot today,” he said.

“Yes,” I told him. “That’s what I heard.”

WE HAD A STRANGE MIX of guys on our crew that year. There were just three regulars – me, JC and Tom – and then we had summer kids who rotated in and out, a different one almost every day. Tom was our foreman. He did the estimates, set up the jobs and made sure that everything kept moving. JC and I laid in most of the stone.

The letters JC stood for Jesus Christ. His real name was Allan but we called him JC because he was born again. Before he came back to real life JC was a paratrooper in the military. He used to jump out of planes. His skin was covered with the kind of tattoos you can only get in the army or in jail. He had the regular naked-woman kind and a couple skulls and some crucifixes with snakes slithering around them. But he had the harder stuff too. Amateur tattoos that looked like a kid had drawn them in. There wer

e a lot of shaky words written out on JC’s body. Some of them were spelled wrong and sometimes the spacing was too tight and you could tell that they had to squish to get all those little sayings to fit inside their separate curling flags. On his back he had a picture of a bomb that was tied up to its own little parachute. It said “Death Comes From Above.” And there was another one that stretched right across the back of his neck, right over the bone of his spine. He had his old unit number there and the little flag said “Pain Is Unavoidable.” But somebody mixed up the O and the I, so it really said “Pain Is Unaviodable.”

JC was a little bit off. Something bad happened to him, I think. Maybe it was in those war simulations or something in the training that’s supposed to break a guy down into just his basic parts. Once, Tom asked JC if he was sure that his parachute opened every time he jumped out of the plane. Tom acted it out for JC. He whistled a windy high note when he thought about JC falling through the air and then he slapped his hands together hard when he thought about him hitting the ground.

“Come on,” Tom said. “Think back. That happened to you at least one time. Whatever it was, you had to get whacked pretty hard to turn out like this.”

JC squinted a lot, like he was always staring into a lamp that was too bright. But I don’t have a bad word to say about him. The guy was completely sound around me except for all his talking about God and the holy scriptures and the coming of the Rapture or whatever. He could really work too, almost like he was powered by the Almighty Lord or some other crazy magic. He could just go and go and go, no matter what time it was, or how hot it was, or if it was raining, or if it was snowing. During his lunch hour he prayed and he read the Bible to us out loud.

The guy was carved up so tight it was like the muscles in his back and his stomach were drawn in with the tattoos. When he took off his shirt, he looked like the worst sort of criminal: the kind in the prison movies who do hundreds of push-ups and sit-ups in their cells. It bothered some of our customers to have him around. The young married couples with kids and minivans didn’t want a guy like that working in front of their new houses. JC had a special feel for those kind of people. He could sense them. When somebody looked at him like that, he never let it pass. He always wanted to talk to them, explain his whole life story. Tell them how he’d been transformed.

“You do not need to be afraid of me,” he’d say.

One time he started talking like that to a guy who was watering his lawn while we put in his driveway. The man had been staring at us for a couple of minutes and I remember that he was wearing a green golf shirt and he didn’t have any shoes on.

Right out of the blue JC said to him, “You can change yourself, you know. It doesn’t have to be this way.”

He talked with that funny up and down rhythm that the black preachers have.

“We can change ourselves,” he said. “Just look at me. You have to look if you want to see.”

And then he turned around so the man could read the words and see the pictures on his back.

“I am the proof,” JC said. “I am the proof that you can change. This is the skin of a different man. This is just a shell to remind me of how it used to be. But I am saved now. And you. You can be saved too.”

The guy with the golf shirt just stood there and nodded his head. I don’t think there was anything else for him to do. The hose kept dripping water on the grass and JC kept turning himself around. From where I was standing, I couldn’t tell if the barefoot guy was having a religious experience or not.

Tom tried to smooth things out after that. Whenever he talked to customers Tom was always professional. He told the barefoot guy that we apologized for the inconvenience and that it would never happen again and that we could discuss a discount or something. But later, when I saw him whispering with JC, Tom was back to himself. There was spit foaming at the corners of his mouth.

“You ever do that again,” he said to JC, “and you’re gone.”

Tom was trying to keep himself together, trying to keep it low, but I could hear him breathing hard out of his nose and I could see the way he was trembling all over when he talked. For a second, I thought he might actually haul off and punch JC right there in this guy’s backyard. I was thinking that that would have been good for our reputation.

“We’ll dump you so fast it’ll make your head spin,” Tom told JC. “And then what’ll you do? Where would you go then? Nobody else would take you.”

Our company worked guys who couldn’t get any other kind of work. Garlatti, our boss, he looked for people like JC and like Tom. Guys who were desperate for a job or stuck because of something they did a long time ago. I worked with Tom for years but I never found out what happened with him. I heard he beat somebody up. Somebody close to him. His wife or his girlfriend or one of his kids, I think, from before. He lived by himself now but I think he still had to pay out almost all the money he made. Tom had to take lots of days off because he was always going to court or to these meetings with some officer who was supposed to keep track of him.

I ate my lunch with Tom every day and every day it was the same thing. At exactly 11:30 he’d go to the back of the truck and haul out his little red cooler. He’d open it up, bring out the cold six-pack, and then he’d drink every one of them in less than half an hour. In all that time, I never saw the guy eat food during lunch. And every day – every single day that we worked together – he made a point of offering that last beer to me, just because he knew I had to stay away from that stuff.

“Come on, Jimmy,” he’d say and he’d wave the last can in front of me. Back and forth and then back and forth another time. “What the hell difference does it make now. You’re past all that.”

In the beginning Garlatti paid us absolutely nothing. But every once in a while he softened up a bit. He used to give us these secret raises that we weren’t supposed to tell anybody about. One week your check would be fifty or seventy-five dollars bigger and when he handed it to you he’d give the paper a little extra push into your hand so that you’d know not to open it in front of everybody else. That’s how he kept his regulars for so long. We kept coming back every week, waiting for that extra fifty bucks to show up.

IT WAS DIFFERENT for the kids though. Garlatti paid them the straight minimum wage and he never budged on that. The man never paid out one cent more than he had to. In the beginning, some of the students tried to pretend that hauling bricks was simply good exercise. Like they figured that if they had to work a bad summer job then they might as well get a tan or get in shape when they were doing it. Guys like that never lasted. Before we got Robbie, Tom must have hired and fired 50 kids, almost one a day since the beginning of the summer.

The job was simple. Carrying bricks, that was it. Carrying bricks all day long and shovelling a little gravel here and there. The kids had to run new brick off the pallets and wheelbarrow away the scraps and the cut pieces. It was their job to keep us stocked up all the time so that me and JC could lay it in nonstop. At first, most of them thought the job couldn’t be that hard. But when we needed to, me and JC could lay it down pretty quick. Back and forth, as fast as fast. Somedays, if we got a feeling for it, we could knock off three driveways or maybe five backyard patios.

The kids usually came out in the morning, worked with us for a day, and then quit when we brought them back in the afternoon. It was the best thing for all of us. They didn’t even come back at the end of the week to pick up their money. Garlatti was smart. He probably pulled a couple hundred hours of free work from that one little piece of paper he had stuck to a bulletin board down at the employment centre. It was like we had a never ending supply of kids to break down.

But Robbie was the last one we hired that summer. He started on the fifteenth of June and he worked right through to the beginning of September. His sunburn cleared up after a while. For the first couple weeks, when his skin was peeling off, he looked kind of scaly, like he was changing into some sort of lizard guy from a screwed-up experiment

, but by the end of the summer he was back to normal. He never took off his shirt again though, so I don’t know what kind of scars he got left with.

“Look at him,” Tom said to me once.

It was on that second day, in the afternoon, and Robbie was running, I mean really running, with these bricks. He piled them up between his arms and carried them in stacks of seven or eight. He held the bottom one with his fingers and the top one tucked in just under his chin. Robbie moved with these quick jerky steps. There was nothing smooth about him. He was always halfway between standing up and crouching down.

Anyone who’s ever done this kind of work can tell you that the bending over is the worst part of it. Bending over and getting up, and then bending over and getting up again – it’s like you’re folding and unfolding your body all day. You get creaky. And just that little bit of weight – just the weight that’s in a couple bricks – that’s enough to grind you down. Any kid can pick up a hundred pounds if they only have to do it one or two times. But it’s the light lifting that does the real damage. Maybe it’s just thirty pounds and it starts off slow, but it stays with you all day and then it hangs around in your arms and your legs even after you leave. That kind of lifting hits you in the knees first and then in your shoulders and your neck. It used to surprise our summer student kids. It would catch them off-guard, usually in the early afternoon, just after lunch. One minute they’d be loud and laughing and tossing the brick around like it was nothing and then, all of a sudden, that little grinding pain would wind up and get a hold of them. You could almost see it tightening around them. It was like they got old all at once. They’d hunch over and get really quiet and start concentrating on the smallest things, trying to figure out what went wrong.

Light Lifting

Light Lifting