- Home

- Alexander Macleod

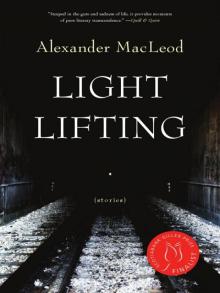

Light Lifting

Light Lifting Read online

LIGHT LIFTING

LIGHT

LIFTING

(stories)

Alexander MacLeod

BIBLIOASIS

Copyright © 2010, Alexander MacLeod

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

FIRST EDITION

Second printing, October 2010

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

MacLeod, Alexander, 1972-

Light lifting / Alexander MacLeod.

ISBN 978-1-897231-94-4

I. Title.

PS8625.L445L54 2010 C813’.6 C2010-904592-0

Biblioasis acknowledges the ongoing financial support of the Government of Canada through The Canada Council for the Arts, Canadian Heritage, the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP); and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Arts Council. The author would like to thank the Canada Council and the Nova Scotia Ministry of Tourism and Culture for their financial support.

PRINTED AND BOUND IN CANADA

For Crystal

Contents

Miracle Mile

Wonder About Parents

Light Lifting

Adult Beginner I

The Loop

Good Kids

The Number Three

Miracle Mile

This was the day after Mike Tyson bit off Evander Holyfield’s ear. You remember that. It was a moment in history – not like Kennedy or the planes flying into the World Trade Center – not up at that level. This was something lower, more like Ben Johnson, back when his eyes were that thick, yellow colour and he tested positive in Seoul after breaking the world record in the hundred. You might not know exactly where you were standing or exactly what you were doing when you first heard about Tyson or about Ben, but when the news came down, I bet it stuck with you. When Tyson bit off Holyfield’s ear, that cut right through the everyday clutter. All the papers and the television news shows ran the exact same pictures of Tyson standing there in his black trunks with the blood in his mouth. It seemed like everything else that happened that day had to be related back to this, back to Mike and what he had done. You have to remember, this was before Tyson got the tattoo on his face and the rematch with Holyfield was supposed to be his big comeback, a chance to go straight and be legitimate again. Nobody thinks about that now. Now, the only thing you see when you look back is Mike moving in for the kill, the way his cheek brushes up almost intimately against Evander’s face just before he breaks all the way through and gives in to his rawest impulse. Then the tendons in his neck bulge out and his eyes pop wide open and his teeth come grinding down.

Burner and I were stuck in another hotel room, watching the sports highlights churn it around and around, the same thirty-second clip of the fight. It was like watching the dryer roll clothes. Cameras showed it from different angles and at different speeds and there were lots of close-ups of Evander’s mangled head and the chunk of flesh lying there in the middle of the ring. Commentators took turns explaining what was happening and what it all meant.

The cleaning lady had already come and gone and now we had two perfectly made double beds, a fresh set of towels and seven empty hours before it would be time for us to go. We just sat there, side by side, beds three feet apart, perched on top of our tight blankets like a pair of castaways on matching rafts drifting in the same current. Mike kept coming at us through the screen. You know how it gets. If you look at the same pictures long enough even the worst things start to feel too familiar, even boring. I turned the TV off but the leftover buzz hanging in the air still hurt my eyes.

“Enough?” I asked, though I knew there’d be no response.

Burner didn’t say anything. His eyes were kind of glossed over and he just sat there staring straight into the same dark place where the picture used to be. He’d been fading in and out for the last few hours.

If I have learned one thing through all this, it’s that you have to let people do what they’re going to do. Everybody gets ready in their own way. Some guys play their music loud, some say their prayers and some can’t keep anything down and they’re always running to the toilet. Burner wasn’t like that. He liked to keep it quiet in the morning, to just sit around and watch mindless TV so he could wander off in his mind and come back anytime he liked. One minute, he could be sitting there, running his mouth off about nothing, and then for no reason, he’d zone out and go way down into himself and stay there perfectly silent for long stretches, staring off to the side like he was trying to remember the name of someone he should really know.

It didn’t bother me. Over the years, Burner and I had been in plenty of hotel rooms together and by now we had our act down. I didn’t mind the way he folded his clothes into perfect squares and put them into the hotel dresser drawers even when we were staying a single night, and I don’t think he cared about the way I dumped my bag into a pile in the corner and pulled out the things I needed. You have to let people do what they do. When you get right down to it, even the craziest ritual and the wildest superstition are based on somebody’s version of real solid logic.

After fifteen minutes of nothing, Burner said “I’m not going to wear underwear.”

He was all bright and edgy now and his eyes started jumping around the room. He licked his top lip every few seconds with just the tip of his tongue darting out.

“No, not going to wear underwear.”

He nodded his head this second time, as if, at last, some big decision had finally been made and he was satisfied with the result.

I didn’t say anything. When he was this far down, Burner didn’t need anybody to keep up the other end of the conversation.

“You feel faster without underwear, you know. But I only do it once or twice a year. Only for the big ones.”

That was it. A second later he was gone again, back below the surface, off to the side.

I turned away from him and punched a slightly bigger dent into my pillow so there’d be more room for my head. I knew there was no chance, but I still closed my eyes and tried to sleep. The alarm on the table said it was 12:17 and no matter what you do you can’t trick those early afternoon numbers. Every red minute was going to leak out of that clock like water coming through the ceiling, building up nice and slow before releasing even one heavy drop. I waited, and I am sure I counted to sixty-five, but when I looked back 12:18 still hadn’t come down. I flopped over onto my back and looked at the little stalagmites in the stucco. I thought about those little silver star-shaped things that are supposed to go off if there’s a fire.

I’ll tell you what I was wearing: my lucky Pogues T-shirt for the warm-up, a ratty Detroit Tigers baseball cap, the same pair of unwashed shorts that had worked okay for me last week and a pair of black track pants that weren’t made of cotton, but some kind of space-age, breathable, moisture-wicking material. On my left foot, I had one expensive running shoe that Adidas had given me for free. Its partner was on the floor beside the bed and I had about a dozen other pairs still wrapped in tissue paper and sitting in their boxes at home. My right foot was bare because I had just finished icing it for the third time that morning. The wet ziplock bag of shrunken hotel ice cubes was slumped at the end of my bed, melting, and my messed-up Achilles was still bright red from the cold. I could just start to feel the throb coming back into it.

I meshed my fingers together on my chest and tried to make them go up and down as slowly as possible. It was coming and we were waiting for it. The goal now was to do absolutely nothing and let time flow right over us. It would h

ave been impossible to do less and still be alive. I felt like one of the bodies laid out in a funeral home, waiting for the guests to arrive. You couldn’t put these things off forever. Eventually it had to end. In a couple hours, some guy dressed all in white would say “Take your marks.” Then, one second later, there’d be the gun.

I DON’T KNOW how much time passed before Burner hopped off his bed like he was in a big rush. He went around our room cranking open all the taps until we had all five running full blast. There were two in the outside sink, the one by the big mirror with all the lights around it, two in the bathroom sink and one big one for the tub. Burner had them all going at once. Water running down the drain was supposed to be a very soothing sound that helped you focus and visualize everything more clearly. This was all part of thinking like a champion. At least that’s what the sports psychology guys said and Burner thought they were right on.

There was a lot of steam at first and we had our own little cloud forming up around the ceiling, but after a while, after we’d used up all the hot water for the entire hotel, the mist cleared and there was only the shhhhhhh sound of the water draining away. It was actually kind of nice. You could just try and put yourself inside that sound and it would carry you some place else, maybe all the way to the ocean.

When Burner surfaced for the last time, when he came back for good, he looked over at me and said, “Do you know what your problem is?”

I took a breath and waited for it.

“You can’t see,” he said.

“You don’t have vision. If you want to do this right, you need to be able to see how it’s going to happen before it actually happens. You have to be in there, in the race, a hundred times in your head before you really do it.”

I nodded because I had to. This season, unlike all the others, Burner was in the position to give advice. For the last three years I had beat him from Vancouver to Halifax and back a hundred times and in all that time I had never said a thing about it. He’d never even been close. But this year – the year of the trials, the year when they picked the team for the World Championships and they were finally going to fund all the spots – this was the year when Burner finally had it all put together at the right time and I couldn’t get anything going. For the last eight weeks, in eight different races in eight different cities, he’d come flying by me in the last one-fifty and there was nothing I could do about it.

I don’t know where it came from or how he did it, but Burner had it all figured out. For the last year he’d been on this crazy diet where it seemed like he only ate green vegetables – just broccoli and spinach and Brussel sprouts all the time. And he hadn’t had a drop of alcohol or a cup of coffee in months. He said he had gone all the way over to the straight edge and that he would never allow another bad substance into his body again. He broke up with his girlfriend and quit going out, even to see a movie. He drank this special decaffeinated green tea and he shaved his head right down to the nut. I think he weighed around 125 or 130. He practiced some watered-down version of Buddhist mysticism and he was interested in yoga and always reading these books with titles like “Going for Gold!: Success the Kenyan Way,” or “Unlocking Your Inner Champion.” Whatever he was doing, it was working. Out of all that mess, he had found some little kernel of truth and now he was putting it into action.

“The secret is to think about nothing,” he said.

“Just let it all hang out. Mind blank and balls to the wall. That’s all there is. Keep it simple, stupid. Be dumb. Just run.”

IT’S HARD TO TELL anybody what it’s really like. Most people have seen too many of those CBC profiles that run during the Olympics, the ones with the special theme music and the torch and all those fuzzy soft camera shots that make everyone look so young and radiantly healthy. I used to think – everybody used to think – they were going to make one of those little movies about me, but I know now it’s never going to happen. It’s timing. Everything is timing. I was down when I needed to be up. If we were both at our best, if Burner and I were both going at it at the top of our games, he would lose. We both knew this. My best times were ahead of his, but I was far from my best now. There were even high-school kids now, coming up from behind and charging hard. I don’t really know what I was waiting for in that room. I might cut the top five, maybe, but I knew I wouldn’t be close enough to be in the photograph when the first guy crossed the line. It wasn’t really competition anymore. For me, this was straight autopilot stuff, going through the motions and following my own ritual right through to the end.

“What about Bourque?” I said.

This was the last part for Burner. I’d say the name of a guy who was going to be there with us and he would describe the guy’s weaknesses. Burner needed to do this, needed to know exactly why the others could not win. There were maybe ten people like us in the whole country, and no more than five or six who had a real shot at making the team, but Burner needed to hate all of them. That was how he worked. I couldn’t care less, but I did my part. I kept my eyes on the sprinklers and didn’t even look at him. I just released the words into the air. I let Bourque’s name float away.

“Bourque? What is Bourque? A 3:39, 3:40 guy at the top end of his dreams. We won’t even see him. Too slow. Period. We won’t even see him.”

“Dawson is supposed to be here,” I said. He was the next guy on the list.

“He ran 3:37.5 at NC’s last month.”

“Got no guts,” Burner sort of snorted it.

“Dawson needs everything to be perfect. He needs a rabbit and a perfectly even pace and he needs there to be sunshine and no wind. He can run, no doubt, but he can’t race. If you shake him up and throw any kind of hurt into him, he’ll just fold. Guy’s got tons of talent, but he’s a coward. You know that, Mikey. Everybody knows that about Dawson. Even Dawson knows it, deep down. If somebody puts in a 57 second 400 in the middle of it, Dawson will be out the back end and he’ll cry when it’s over. He will actually cry. You will see the tears running down his face.”

“Marcotte will take it out hard right from the gun,” I said. “He’ll open in 56 and then just try and hold on. He’s crazy and he will never quit. There’s no limit to how much that guy can hurt.”

“But he can’t hold it. You know how it’ll be. Just like last week and the week before. It’ll be exactly the same. Marcotte will blow his load too soon and we’ll come sailing by with 300 to go. If we close in 42, he’ll have nothing in the tank. He’ll collapse and fall over at the finish line and somebody will have to carry him away.”

THAT’S HOW WE TALKED most of the time. The numbers meant more than the words and the smaller numbers meant more than the bigger ones. It was like we belonged to our own little country and we had this secret language that almost nobody else understood. Almost nobody can tell you the real difference between 3:36 and 3:39. Almost nobody understands that there’s something in there, something important and significant, just waiting to be released out of that space between the six and the nine. Put it this way: if you ever wanted to cross over that gap, if you ever wanted to see what it was like on the other side, you would need to change your entire life and get rid of almost everything else. You have to make choices: you can’t run and be an astronaut. Can’t run and have a full-time job. Can’t run and have a girlfriend who doesn’t run. When I stopped going to church or coming home for holidays, my mother used to worry that I was losing my balance, but I never met a balanced guy who ever got anything done. There’s nothing new about this stuff. You have to sign the same deal if you want to be good – I mean truly good – at anything. Burner and I, and all those other guys, we understood this. We knew all about it. Every pure specialist is the same way so either you know what I am talking about or you do not.

“In the end, it’s going to come back to Graham,” I said. I’d been saving his name for last.

“Graham,” Burner repeated it back to me.

“Graham, Graham, Graham, Graham.”

It sounded

almost like a spell or a voodoo curse, but what else could you say? We both knew there was no easy answer for Graham.

WHEN WE WERE KIDS in high school, back when we first joined the club and started training together, Burner and I used to race the freight trains through the old Michigan central railway tunnel. It was one of those impossible dangerous things that only invincible high school kids even try: running in the dark, all the way from Detroit to Windsor, underneath the river. When I think back, I still get kind of quaky and I can’t believe we got away untouched. It didn’t work out like that for everyone. Just a few years ago, a kid in the tunnel got sucked under one of those big red CP freighters and when they found him his left arm and his left leg had been cut right off. Somehow he lived, and everybody thought there must have been some kind of divine intervention. The doctors managed to reattach his arm and I think he got a state-ofthe-art prosthetic leg paid for by the War Amps. The papers tried to turn it into a feel good piece, but all I could think about was how hard it would be for that kid to go through the rest of his life with that story stuck to him and the consequences of it so clear to everybody else.

Burner and I used to race the trains at night from the American side, under the river, and up through the other opening into the CP railyard, over by Wellington Avenue, where all the tracks bundle up and braid together. At that time, before the planes flew into the World Trade Center, there weren’t any real border guards or customs officers or police posted on the rail tunnel. They just had fences. On the American side you had to climb over and on the Canadian side someone had already snipped a hole through the links and you could just walk. The train tunnel is twice as long as the one they use for the cars and I think we had it paced out at around two and a half miles or about fifteen minutes of hard blasting through the dark, trying not to trip over the switches or the broken ties or the ten thousand rats that live down there.

Light Lifting

Light Lifting