- Home

- Alexander Macleod

Light Lifting Page 6

Light Lifting Read online

Page 6

How much do you think? she asks me once.

Blazing sunlight. Grey hand-job puddle in her palm. Devious, joking smile.

She holds it out. Slime on her fingers.

How much do you think? In one lifetime? How much can one guy produce? A pint of it? A gallon of splooge? No way. Think about that: a gallon, a milk jug in just one person? So, so, so gross.

What we will or will not do. She spits. It’s like a spoonful of salty, spicy snot.

THEY PROVIDE US with choices. Second options. Back door solutions. Science and witch doctor stuff. In vitro. Voodoo remedies. Test tubes. Special teas. Surrogates. Yoga. Deep breathing. Are you too hot down there? Too tight? Forms to fill out for adoption. Somebody else’s trip back from a Chinese orphanage. Maybe it will be just ourselves. And can you please tell me what would be so wrong with that? A clean house. Newspapers read cover to cover. Film festivals. Money. We might have money. Maybe just ourselves. Think about that for a second. Could we stay like this all the way through?

No, she says. No.

Twenty-six months of trying. But only twenty-six. Positive test result. Nobody can tell us why. Sometimes these things happen, they say. Sometimes. Zygote. Meiosis. Change. A series of diagrams I remember from a high-school Biology test. Still with me. Chromosomes pulling to the side, dividing on their own. Hold that stick directly in the stream of your urine. Wait for it. A mark emerging from the white background. Plus sign.

Zinsser. My crazed epidemiologist. How much I like him: “But the louse seems indefinitely committed to the materialistic existence, as long as lousy people exist. Each newborn child is a possible virgin continent, which will keep the louse a pioneer – ever deaf to the exhortations to better evaluate his values. If lice can dread, the nightmare of their lives is the fear of some day inhabiting an infected human being.”

The night off. Home for Christmas and everybody else in bed. The baby goes down easy. Nervous energy from the road. Hit The Bridge with my brothers. Bring it on. Pitchers of draft and over-salted stale popcorn. There is never enough. Stay through to close. Rush to pay. This is on me. The next pitcher and a round of shots. Deep swallows and sour faces. Accept all obvious consequences for our actions. See the future. What is going to happen to us: Stagger back home, compete for couches. Sleep on the floor for two or three hours. Wake to the same hard morning. The world starting up again. My brain and your brain and your brain. Same hangover beating in every head. Know you will throw-up hours before you actually do.

Talk about nothing. Talk only for the voices, the sounds they make. The way they hold the table together. A good topic is all you need. Best nickname in the history of the Pistons.

Has to be The Worm.

Well, that sucks. He probably got it right there.

Might have to stop before we start.

You can’t beat that. A professional athlete who called himself The Worm. We’re talking the early Rodman here. Before the Bulls and the piercings and the multi-coloured hair. Before Madonna. Just a skinny freak of nature going up for the ball, boxing out guys six inches taller than he was. He gave up at least forty pounds every single night and still nobody could stop him. Defensive Player of the Year a million times. Crazy.

They had Spider Salley back there, too. All arms and legs. Coming off the bench. The front court was full of bug names.

James Buddha Edwards?

Nobody, nobody, worked the Fu Manchu better than that guy. It looked normal on him.

And you think Rodman was skinny, what about Tay Tay?

I like the way George Blaha says his name: “Tayshaun scoops it and he scores it.”

Even Blaha kind of works when you think about it.

Yeah. Blaha is a possibility. You just leave it out there by itself: The Bla and then the Ha.

That’s not a nickname, though, right? Blaha is his real name.

Fuck you.

Big Ben is too obvious. Swinging his sledgehammer with his homegame Afro teased all the way out.

‘Let’s go to work.’ That was perfect.

Or Zeke. Remember when Isiah did those public service announcements for Detroit Edison. I guess they were trying cut down on accidental childhood electrocutions.

– Hey kids, look up.

– But, Isiah, I don’t see anything.

– That’s good, because there might have been power lines.

He was off the charts for the unintentionally hilarious.

Mahorn and Laimbeer. Evil sons of bitches. The real bad boys. Kept knocking Jordan on his ass for years and years before he got through.

And the new guys: Rip and Sheed and Chauncey.

Mr. Big Shot.

Rasheed bought an actual heavy-weight championship belt for every guy after they won. Said he’d take his five against any other five in the world.

He, Sheed, is the absolute greatest of all time. The G.O.A.T. Unstoppable whenever he felt like trying. Seven feet tall. Shooting the threes and taking the T’s.

Best nickname in the history of the Pistons. Should have thought of it sooner: Vinnie Johnson.

A moment of silence. We nod our heads because this is true. There is no need to proceed.

Bigger than the Pistons, really, when you think about it.

Probably the best nickname in the history of sports.

Vinnie – The Microwave – Johnson.

Awesome.

It is time for the Microwave.

Remember that?

I most certainly do.

We need the Microwave right now.

His jump shot moved against the laws of physics.

How could that work? A line drive with no arc whatsoever.

I don’t care how or why it worked. Just know it always went in.

Yep.

Put him in stone cold and he heats up to a scorching inferno in less than a second.

That’s why they call him the Microwave.

Because he bringeth the heat.

Vinnie could sit on the bench for three and a half quarters doing nothing. He could be there in his street clothes and a pair of loafers, clapping his hands and telling jokes.

You put him in only when you need him.

Game on the line, down by four, three minutes left. Chuck makes the call.

Then, Boom, The Microwave goes off for 12 points down the stretch. He makes two threes and draws a charge on the other end. The starters sit to make room for him.

He’s the guy who will walk to the line and sink both free throws to win it at the end, even when all the time has expired.

I want to propose a toast to the Microwave.

Yes. To Vinnie Johnson. For all he’s given us.

To the Microwave for always delivering when it counted.

You can live a long, long time, but you will never see anything else like that.

Not the Romans or the Mongol hordes. Not Alexander, or the Crusaders, or the Spanish Armada, or Napoleon and the Nazis. No one was ever strong enough. All brought down in the end. This is Zinsser’s true fascination. The history of the world indexed to the life of an insect: “this creature which has carried the pestilence that has devastated cities, driven populations into exile, turned conquering armies into panic-stricken rabbles.” Lenin, during the revolution, millions dying around him. The outcome unsure. He doesn’t know what is going to happen. It hangs in the balance. He says: Either socialism will defeat the louse or the louse will defeat socialism.

All the lights on in our house. Three in the morning. Something wrong. We come up the stairs and they are all waiting. She stands between my mother and father. The baby completely white now. Skin almost translucent. Purple eyelids. Lips dry and orange.

She threw up red, she says.

We have to go to the Hospital. You hold her and I’ll drive.

Emergency room at Christmas time. Tree in the corner with a sign. These gifts are empty boxes. Please refrain from opening.

Rows of moulded seats with metal arm rails that make it impossible

to lie down. A Saturday night crowd during the holidays. Woman with plastic bag socks. She has a shopping cart full of empty pop cans parked outside the sliding door. A guy sleeping across from us, legs splayed wide like an upside down “Y.” Small separate bruises on the right side of his face. Ambulances rolling in and out. Stretchers. Overdoses. Bar fights. A man with a knife stuck right through his hand. Nurse tells him to leave it in and wait for further instructions. Triage.

We fill out our forms and huddle. Health Cards from a different province. Suspicion. You may have to pay for this up front and get reimbursed when you return home. Her temperature keeps rising. Wheezing when she breathes. Brown pus around her eyes. They take blood and urine samples right away. Then we wait.

Five hours. Six.

The light of the next day comes up. Regular staff arrive with coffee and their bagged lunches. Smile at each other. Talk about good two-for-one sales at the mall last night. The folding corrugated wall around the gift shop is opened up and the cash register blinks to life.

We take turns holding her. Passing the limp body back and forth. She hasn’t opened her eyes all night. No sign of Vinnie Johnson.

Talk to them, she says. What is going on? They think they’ve called us. They think they’ve already called, but they haven’t. They have our results by now. They have to have them. We’ve been here all night. Our file must be in the wrong place. Nobody would leave a baby out here, in this room, for an entire night at Christmas. Go talk to them.

At the desk, I say, do you think we can take our baby home, please, and maybe you can call us with the results? I don’t think you fully understand the situation. We’ve been here for hours with a newborn and nothing is happening. Nobody has even checked on her.

At that moment, a doctor comes through the swinging doors and calls our name.

The nurse points at me.

Right there, she says. They want to know if they can go home.

He pulls the results out of a pile and looks me over. The same clothes for two days. The stink of the drive. No toothbrush or razor. He can smell The Bridge all over me.

This child, he says, flipping the pages of the report, stretching it out. This child is not going anywhere.

He slams his clipboard down on the counter of the nurse’s station. The swack brings the attention of the whole room onto my back. His eyes are furious. I am one of a hundred. There are a hundred every night. A thousand nights in a row.

This child, he says, and he points at her name, a purple impression on the top of a form, is very, very sick.

He waits. Breathes in and breathes out.

This child is seriously ill and she needs to be admitted to this hospital right away. She will be admitted into the paediatric intensive care unit. That is where she needs to be, sir. Not going home with you. We know what she needs. You, sir, you are the person who does not fully understand the situation.

We glare at each other. I sway in my own exhausted stench. Close my eyes for one second. I know what I look like.

Or I can call child services if you prefer, he says. We can start a file.

DDT was supposed to be the miracle cure. The end of Typhus and Malaria. Cheap and available everywhere. They sprayed it directly onto people’s heads, into their armpits. Clothes fumigated. Whole houses. Beds, and pillows, and sheets. Utensils, cookware. Entire populations disinfected. They called it the pesticide that saved Europe. Guy got a Nobel Prize for inventing it. Total extermination. The side effects go unnoticed until it is too late. Already deep in the food chain. A half-life of 33 years in nature. Toxicity building up through each stage, passed from organism to organism. Ground water, rivers and lakes. Grains. Cash crops. Poultry and Fish and Reptiles. Endangered Species. Infected crocodiles and alligators, Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons. They lay eggs with thin, almost transparent shells. No protection. Causes infertility in humans. Breast cancer. Miscarriages. Low birth weight. Developmental delays. Numbers too high to count. But lice adapt. They go on. Become resistant. Completely unaffected by DDT now. Not like us. Trace amounts of it in every single person’s blood.

Chronic kidney disease. Dangerously low filtration rate. Advanced infection. A congenital abnormality.

They strap the baby down. Immobilize her arm on a gauze-covered splint. A resident tries to find the vein for an infant IV. The nurse practitioner watches as the resident jabs and jabs again.

I can’t find it, she says.

We are all watching.

It’s always hard with small kids and babies. Just relax and try again. You’ll get the hang of it eventually.

Two more misses. The resident bites the tip of her tongue. Another failed attempt.

We hold the baby’s other hand. Pet her head. Everything will be okay. Her face contorts. She turns to look at us. Total confusion in her eyes. Betrayal. Why do you do this to me?

The nurse finally says, okay give it here. Then she misses three more times before something happens. She releases the tape and the medicine flows out of its plastic bag.

Make sure she doesn’t pull that out.

She looks at me and I shake my head. They leave.

ULTRASOUNDS AND X-RAYS. Inject a dye into her bladder. Watch her pee on the monitor, the black colour running backwards, up through the malformed valve, snaking along the wrong path back to the shrunken kidney.

You see that? The technician says.

That is a high grade reflux with already extensive scarring. Lucky we caught it when we did. He pushes buttons. Screen captures for her file.

We try to take it all in. Get through to the essential information. Attempts at questions.

So what are we talking about here? I say. Is she going to be okay? How bad is it? We’re not in transplant territory, are we?

She jumps in before he can say anything.

I could give her my kidney, right? One of us. We would have to be a good match. Then she could have a normal life. Be able to run around. I want her to be able to run around. Not sick all the time. We got it early enough, right? You can fix it. She’s going to be fine.

I’m sorry, he says. I don’t know anything. Just run the machine. The doctors interpret the results.

He checks his watch.

Have to wait and see. Could be severe complications or a simple procedure to fix the valve. Function might come right back to normal. You can’t tell anything in the beginning. It doesn’t look good now, but it all depends on how she responds. Could go any number of ways.

No sign of them for two weeks, but we can’t be sure.

It’s done, I say. They’re gone. We made it.

Better be right this time, she says. Can’t take much more.

My brain still teeming. The itch. It doesn’t require proof or evidence. Thought is enough. You do it to yourself. Lice. Imagine them crawling on your head. Claws touching skin. They pass over us, across this family.

I wander the quiet house at night. Think I sense them everywhere, penetrating cushions and clothes and blankets. No place too intimate. Asleep in our bed. Her head against the pillowcase, hair fanned out. The girl with the Clash T-shirt. We get to choose each other, but kids have no say about the nature of their own lives. Two girls and a boy. Dead to the world. Separate beds. Each clutching a stuffed animal. What are we to these people? Genetics. A story they make up about themselves.

Can’t sleep without the stuffies. Essential part of the night time ritual. Sacred objects made in a Bangladesh factory. The soft places where children dump their love for the first few years. Think of the crying and the frantic searches. What happens to us if one of these toys gets lost or left behind at the grocery store.

But the lice creep in. Even here. Wait it out for a chance to come back. I take the battered elephant and the patched monkey and the frayed horse. Pry them out of the kids’ arms without waking anybody up. Bring them downstairs to the basement. Toss everybody into the deep freezer for the night. They sleep on a value pack slab of frozen pork chops. The only treatment guarante

ed to kill.

This is what I have learned from Hans Zinsser. Lice need a regular temperature. Can’t survive extreme shifts. Sensitive to the smallest change in the host. They can tell when it is time to move on. The writing on the wall. A bad fever sometimes enough. Lice know what you don’t. Leave a body voluntarily the second it starts to cool. People who have lived through cataclysms – veterans from the war, victims of earthquakes, those who escaped the camps – they will tell you. Lice, like a cloud, like ink, seeping from the head and the groin of a corpse. Confirmation. They register it first, the cold taste, the stillness. Bodies on the ground, dropped in the exercise yard, leaking their insects.

We take it in shifts. Not smart to burn out two people at the same time. The room has one chair that can fold out into a very narrow single bed. One sits up with the baby, while the other goes home and tries to sleep. My turn, then your turn. Rotation. We pass in the hall sometimes. Exchange Tupperware meals. Concerned families waiting in different houses. The news. What the doctor said this time. Nothing happened today. She had a good night.

Medication. The baby wakes up, starts to come back to herself. Little by little. Gurgling and happy sometimes, but not out of the woods. She reaches out through the metal bars of the hospital crib. Holds my finger.

They have her hooked up to a machine. Tubes and wires. A long strip of paper, like a sales slip, scrolling out. Something inside draws a continuous erratic line over the narrow graph paper. It goes up and down. Sometimes rests for a long plateau. The nurses consult it every time they come in the room. We have no idea what it means. When we ask, they say: more data for the chart. There are numbers, too. Three of them. Two for blood pressure, we think, and then something else. A single flashing light, but no sound. The bulb is purple. Blinks on and off. Fluctuates. A silent rhythm, picking up and coming back down. Her heart, most likely, but it seems too slow sometimes.

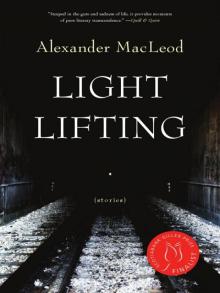

Light Lifting

Light Lifting